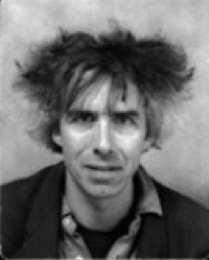

D’HAENE Frederic (1961)

Frederic D’haene, born in Kortrijk in 1961, began his musical education at the music academies of Ghent and Kortrijk. With his sights on a professional music career, he then studied at the Royal Conservatory in Liège, where he was in the classes of Frederic Rzewski and Walter Zimmerman. There he also took lessons from Henri Pousseur and Vinko Globokar. In order to further develop the theoretical aspect of his musical studies, D’haene decided to enter the university programme of musicology, which he started at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and completed at the Rijksuniversiteit Gent. In addition, he took part in the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik in Darmstadt in 1988. Between 1990 and 1995, Frederic D’haene was an assistant teacher in Rzewski’s composition class at the conservatory in Liège. He also taught at the Jette (Brussels) music academy, where he taught courses in musical culture and music history. D’haene has also occasionally been active as a concert organiser (for such organisations as Amnesty International).

An important demarcation in D’haene’s career was the year 1996, when he took a sabbatical. In 1999 and 2000, he taught music aesthetics at the School of Sciences and Art in Ghent. In 2000, D’haene moved to the Netherlands, which allowed him to devote his full attention to composition, with time-pressures weighing less heavily, and with the aid of a well-designed state system which aims to support new music in all its aspects.

Frederic D’haene composes mainly on commission, having produced works for such organisations as deSingel (Antwerp), the Beursschouwburg (Brussels), Antwerp ’93 (European Cultural Capital), Ars Musica – festival ’93, Stichting Logos, Champ d’Action, and the Nouvel Ensemble Moderne de Montréal. A number of these works have been performed by renowned soloists (including Geoffrey Madge, Frederic Rzewski, Marianne Schroeder, Armand Angster, Claude Coppens and Yutaka Oya) and ensembles (Champ d’Action, Ensemble l’art pour l’art, Ensemble Q-O2 and the Phoenix trio). Young and talented Belgian artists, such as Daan Vandewalle, Geneviève Focroulle and Ivan Meylemans, have also performed his often demanding scores. D’haene’s compositions have been played in Brussels, Kiel (Gesellschaft für akustische Lebenshilfe), London (Blackheath Concert Halls) and Edmonton (New Music Festival). Several works have been recorded for CD or for broadcast by such national radio networks as the Belgian Radio (both French and Flemish services), the BBC, the WDR, and the CBC. D’haene is also one of the composers who took part in the “Bruges 2002” project (European Cultural Capital), where the composition Inert Reacting Substance of ( ) received a performance by the Flemish Symphony Orchestra.

Work

The starting-point for D’haene’s thought and composition is the so-called “aesthetics of the desert”: anything goes, or rather, all manner of materials are open to musical treatment. By the same token, this means that no historical musical material is automatically rejected: all has become neutral. The consequences of this are two-fold: either choices are made from this immense array of possibilities, or a quest is undertaken, a never-ending exploration, in which movement itself is the key and where the actual goal is never reached. This explorative element has been present from the very beginning in D’haene’s music, as he has continually investigated different worlds and made a resolute choice for plurality and heterogeneity. Moreover, he has felt no need to favour one particular world or language over another and thereby to attract polemics. In this “desert experience”, the composer feels a certain connection with Edgar Varèse, who, in relation to his work Déserts, remarked that “Déserts signifies for me not only physical deserts, those of sand and those of the sea … which evoke … existence outside of time, but also this distant internal space that no telescope can reach, where man is alone in a world of mystery and essential solitude”. Saint-Exupéry (Terre des hommes) also forms an important source of inspiration for D’haene’s aesthetic: “What is the use of discussing ideologies?”. In general, poets – rather than his composer colleagues – are the most important source of ideas for D’haene, a fact clearly expressed in works such as Pessoa Revisited (1991), in which texts by the famous poet set the tone for the performers’ interpretation and intellectual approach: the opening pages of the score present Pessoa’s text, which is intended to be incorporated into the instrumental part as the guiding element for the interpretation (“Nothing binds me to nothing”); in addition to this, the same performers are expected to sing textless music during the course of the work. In Wozu Dichter – Millimètres (1992), a French Pessoa text (“L’ennui, c’est la sensation physique du chaos”), performed simultaneously by several musicians, blends with a German text by Hölderlin (“Wozu Dichter in Dürftiger Zeit?”). The texts are to be declaimed sometimes aloud, and sometimes silently and inwardly by the musician, even though the text is clearly set under the music staff. It will by now be amply clear that in these works D’haene expects more from the performer than the interpretation of one single, assigned part: rather, the performer must combine this with a percussion part on his or her instrument or on a small percussion instrument, or may be given a vocal part or a text to be read aloud.

Frederic D’haene has a very explicit vision of society, or samenleving, in the literal Dutch sense of “living-together”: all barriers (real or imagined) that separate people from one another – states, religions – should be torn down. Only in this way can different cultures be sources of inspiration for one another. In this regard, Japan has become an important point of reference for the composer over the years. This interest does not take the form of unthinkingly appropriating Japanese folk music, but is rather a total absorption of the Japanese world and tradition, grafted onto many other influences and D’haene’s own language. This results in a true melding of different concepts of culture, according to the idea of “coexistence”. This idea is not based on blind naïveté on the composer’s part, but is immediately put into perspective by D’haene himself: the notion of “composition” itself has a Western-cultural connotation and is always manifested within a tradition. The composer, however, stands against monistic and dualistic conceptions, resolutely choosing pluralism; this explains his preference for the (il)logic of the paradox, another central characteristic of his thought and composition. The paradox is manifested – without coquetry – on all levels of his composition process, from the forming of the concept (coexistence – one’s own tradition / open – closed), to the constructing of the work (unity – fragment), to the smaller elements (particularly evident in the titles of the works: Inert – reacting / dissociations – centromériques).

What do these central aesthetic concepts mean for the compositional techniques applied by D’haene and the concrete way in which he shapes his works? The aesthetic of coexistence appears here as the relationship between unrelated elements (in other words, the postmodernist idea that unity and fragmentedness go hand in hand), while the idea of the paradox cannot be realised as an end in itself, but as a means to an end that is sought after through a continuing exploration of the ways that elements that exclude one another in logical terms can still be “true” when taken together. For D’haene, being “true” in music means being “intense”. All of this has brought Frederic D’haene to the development of his “technique of paradoxical pitch coexistences”, which are manifested in different musical parameters. This can be seen, for example, on the level of harmony: here the composer works with spectral, modal and atonal pitch sequences, where a modal or spectral interval can function simultaneously as an axis for atonal-polarised (fixed in pitch) pitch sequences. The placing of the same interval within different contexts has also been a central concern right from the beginning of D’haene’s composing process. Equally, on the level of rhythm, this coexistence of numerous dimensions can be seen: there is the simultaneity of a constant tempo and changeable tempi (in order to allow the harmonic material to manifest itself as a plurality of dimensions, and not as complete chaos). Finally, on the level of form, there is the simultaneity of control and aleatoric elements, which is expressed in a combination of massive sound and silence, of static and dynamic layers (this may be compared with the work of Paul Klee, an important and direct source of inspiration for D’haene), and of polyphony and heterophony (the polyphony of heterogeneous layers and a heterophony between the layers). The development of this concept was a process of years, during which the composer sometimes consciously changed course: the modal sequences originally found only in slow passages were increasingly presented in quicker tempi. In his early works, the principle of juxtaposition dominated: in his desire for a greater adeptness in linguistic technique, the composer would later begin to place more and more layers one above the other, so that successivity and simultaneity could be brought to a new equilibrium in a cruciform structure. The fascination for sustained sounds from his early period has today yielded to an interest in any element that moves and changes. Finally, the original combination of different layers of text has given way to working with different sorts of layers (including those on the level of tempo, rhythm and pitch constellations).

The idea of the paradox is nicely illustrated in Dissociations centromériques (one of the first works written after his sabbatical). The title of this concerto for piano, percussion and chamber orchestra already carries with it a degree of tension, as it combines elements that fall apart (dissociation) with elements that seek the middle point (centromériques). In Hearing from Nowhere – part 2, D’haene again works with multiple layers and axes. A fundamental tone sounds continuously, while at the same time being able to change in function (the use of a sustained tone is characteristic of D’haene’s whole oeuvre); a second layer is formed by the material for flute, piano and violin, which continuously produce the same intervals (often in mirror image), but in differing orders. Within the piano part, there is, moreover, a further differentiation into two differing tempo layers, by means of which the whole is carried forward by two pulses. Finally, the modal sequences also constitute a separate layer. The composer is careful to ensure that this construction does not degenerate into an impenetrable chaos, but rather that the independence of the different dimensions remains intact (polyphony – heterophony). A look at the score and the scoring (with a central role given to the percussion) throws further light on a very concrete element of Frederic D’haene’s thought and composition, the domination of rhythm. In this composer’s music, a rhythmic cell often forms the point of departure: an interesting rhythmic idea is notated as precisely as possible, then worked out (using techniques such as augmentation and diminution), and interwoven with pitch-layers. This material then undergoes a (non-linear) process of dismantling, recapitulation, anticipation, and so forth, until it becomes a structure that is characterised by sharp changes in density, in which there is also room for absolute silence (a “black hole”). Despite the complexity of the rhythmic texture thus created, D’haene unwaveringly chooses to continue to notate everything in order to give the performer something to hold on to; this does not mean, however, that the aspect of freedom is completely absent. A playing technique developed by D’haene himself (glissandi combined with rhythmic, clearly indicated string crossings), reconciles an exact notation with a certain degree of artistic freedom, resulting in a “controlled aleatoric quality”.

For Frederic D’haene it is important to keep the aim and the function of “art” constantly in view: art must fascinate, but also “teach conceptually”; art must generate new concepts in order to be able to interpret the world of today, in order in turn to keep us from holding on too firmly to the concepts and language of yesterday.

List of works

Chamber music: Communio for 2 piano’s (1989); Sans identité for quartet of bass clarinets (1991); Pessoa revisited for flute, cello and piano (1991); Wozu Dichter — Millimètres for soprano, flute, cello, piano and obligate percussion (1992); Objets retrouvés pour la collectivité for two trombones (1992); A-centroid for string quartet (1993); Inert reacting substance of ( ) for chamber orchestra (1993); Hearing from nowhere – part one for flute, bass clarinet, viola, cello, percussion and piano (1994 [work in progress]); Dissociations centromériques for piano, percussion and chamber orchestra (1997-1998); Poet of liberty for soprano, flute, cello, piano and obligate percussion (1998-1999); Hearing from nowhere – part 2 for fluet, bass clarinet, percussion, piano, violin and cello (2000); Désert axiomatique for percussion and string quartet (2001)

Symphonic orchestra: Scorci dei Mocciolo for rockcombo and symphonic orchestra (1995)

Works for solo instrument/voice: For declining times for piano solo (1990); The peaks were…The valleys came in — Musik für Lara for piano solo (1992); Brief an Kandinsky for bass clarinet solo (1992); MusicAnarchy I — to Breathe that void for solo voice (1998)

Electronic music: Ohne Titel — Mit Text for soprano, piano, strings and tape (1990)

Music for choir a cappella: Allelujàssemblage (1991)

Music theater: Muziektheater «tirannie der hulpverlening» for fluet, trombone, harp, percussion and two actors (1991)

Since 1992: Trilogyfragments: big cycle of seven pieces, to which already four of the above mentionned belong (work in progress)

Bibliography

– KNOCKAERT, art. Frédéric D’Haene, in M. DELAERE, Y. KNOCKAERT en H. SABBE, Nieuwe muziek in Vlaanderen, Brugge, 1998, p.156-158

©MATRIX

Texts by Sofie Taes

Last update: 2002

www.fredericdhaene.be

frederic.dhaene@freeler.nl

de Vang 51, 6581 DP Malden (Nederland)

0031 (24) 355 21 57